The making of Volvo's crystal glass gearsticks

Amid all the high-tech, some Volvos have an exquisite gear selector made using processes and skills that are centuries old

When the glassworks in the small Swedish town of Kosta was founded, its owners didn’t foresee it would one day make gear selectors. It was 1742, after all, when demand for car parts was somewhat limited.

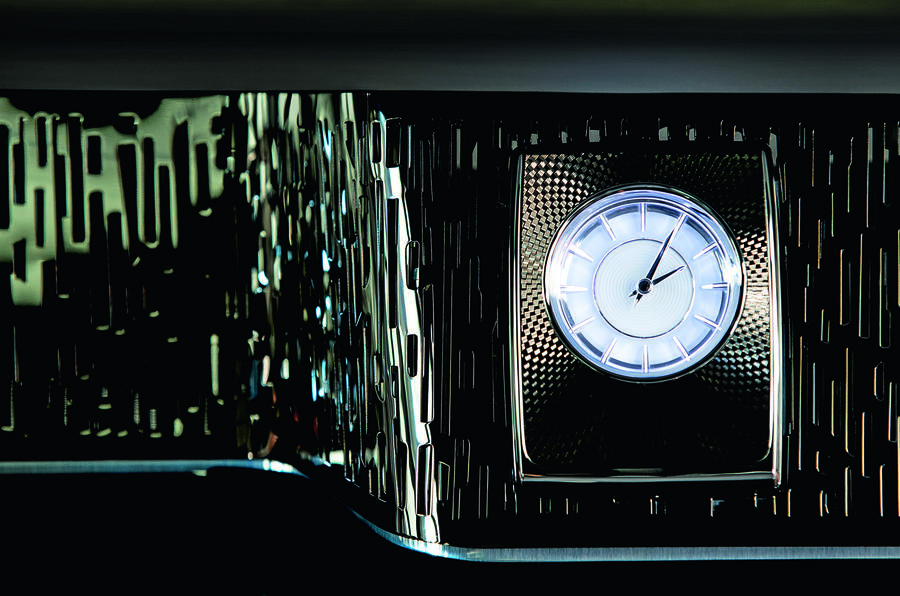

Yet 277 years later, Kosta’s hot shop is an unlikely hotspot for the production of Volvo gear selectors. Not regular gear selectors, of course: Orrefors Crystal Eye units are handmade from crystal glass, forged and shaped using tools and techniques that are near identical to those employed in the 18th century.

They’re beautiful, terribly fancy and, of course, entirely unnecessary: swapping a regular selector for a glass one doesn’t improve the shift times of an XC90 Inscription at all. But they’re increasingly popular and Volvo is widening their availability in its range.

“I loved the idea of taking something from outside the industry and bringing it into a car,” says Anders Bergström, Volvo’s colour and materials designer. “We wanted to build on our Scandinavian heritage, which gave me the idea to use crystal glass.”

It has big boots to fill and talented rivals to face. Is it up to the task?

A gear selector works, Bergström says, because “it needed to be a big lump. The beauty of crystal glass is that you see it come alive. The gear selector is in the centre of the car and you touch it, so you feel the material and enjoy it that way as well.”

Amazingly, it took 10 years to turn that idea into reality. To find out why, we headed deep into rural Smaland, the heart of Sweden’s Glasriket – the Kingdom of Crystal.

Natural resources – silicon-rich sand and ample forests to provide fuel – nourished the glass industry there and dozens of glassworks are dotted around the region.

The town of Kosta is named for the founders of the glassworks there. The nearby town of Orrefors gained its own glassworks in 1898. The Orrefors and Kosta Boda firms merged in 1990 (consolidation isn’t just a car industry trend) and, since 2013, their handmade operations have been combined in Kosta.

The town is, predictably, dominated by the glass industry: the Kosta’s Art Glass Hotel, for example, features a glass bar, glass sculptures of food on the breakfast buffet and glass artwork on the bedside tables (our review: not child-friendly).

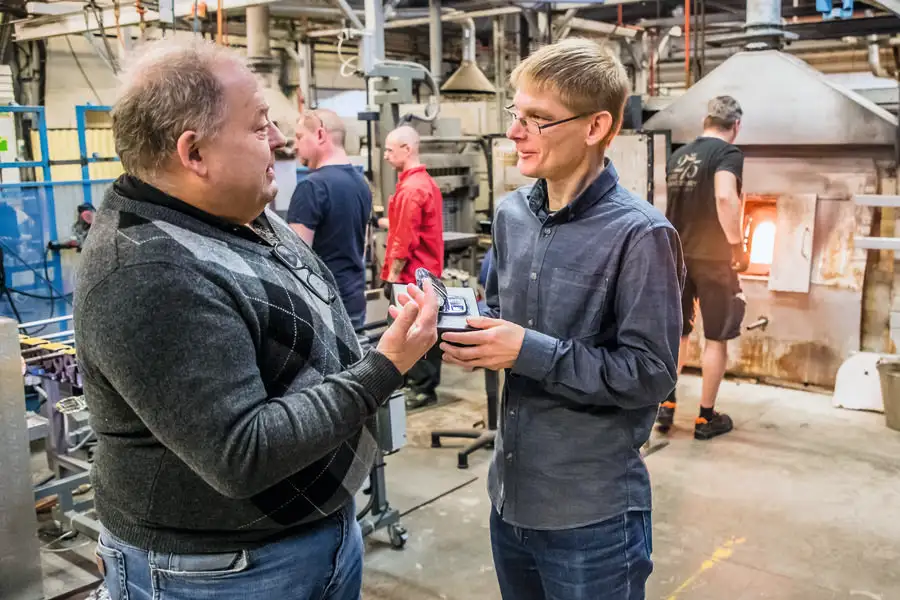

The hot shop is the heart of the Orrefors-Kosta Boda operation. Inside are a number of large furnaces, each of which is the centre of a glass production line. It’s a far cry from a modern car factory, with no robots or automation. Everything is done by hand.

Each furnace is crewed by a team of four and two teams make two types of Crystal Eye: one for the Volvo XC40, and a larger one for the XC60, XC90 and V90. “Bigger cars need a bigger selector,” says Bergström. “It’s a bit posher.”

A glass gear selector starts life as sand. The lead-free pelleted batch is prepared locally by sibling firm Glasma to what Lars Sjögren, head of the Crystal Eye production team, calls “a special secret recipe”. Yes, secret sand. “It’s all about the mix of elements,” says Sjögren.

The first task is to melt the secret sand, which takes 16 hours at 1400deg C and is done in a clay pot in each furnace. Because of the limitations of how much sand can be melted in a pot, each team uses two furnaces, swapping halfway through each day. Once the sand is melted, the oven is turned down: at 1400deg C, molten glass is too hot to work with. At 1180deg C, apparently, it’s just right.

Production begins with a glassmaker expertly hooking a suitably sized lump of molten glass onto the end of a metal rod and carefully lifting it to a bench, where it’s rolled roughly into shape.

It’s formed into its gear selector shape using a cast-iron mould before being placed on a rack. It’s then rotated while it’s moved down a line, variously being cooled by a fan or heated by a flame. It looks random, but it’s science: the process strengthens and polishes the glass.

On a frequent basis, a glassmaker will pause, look closely at the gear selector they’re working on, sigh slightly and then plunge the metal rod into a nearby bucket of water. That’s a rejection and the standards are exacting. The team makes around 50 units an hour, but only 35 or so will make the cut.

According to Sjogren, employees spend at least five years at the firm before they even start to learn glassmaking. Most have been there for decades and focus on a single product. At this stage, I’ve been in the hot shop for about 30 minutes but am still determined to try.

A glassmaker eventually allows me to ‘help’ by carrying a rod loaded with a molten glass selector from one station to the next. He helpfully warns me that it’s hot (although the glowing molten glass on the end is a clue). I feel I’m doing a decent job of twirling the selector, although every unit I go near is then dumped straight into the water bucket. I succeed only in bumping up the rejection rate.

The surviving gear selectors are placed into an annealing lehr, a sort of oven in which the glass is put through another heating and cooling cycle, emerging eight hours later at room temperature. Then the Orrefors logo is printed on the XC40 selectors and on the larger unit is created inside it in a 3D effect. Sjogren won’t explain how. It’s another secret. Still, the logo is a mark of respect.

Once that’s done, there are more checks by another expert glassmaker, who minutely examines each selector. Next to him is a bin filled with gear selectors that failed to meet his standards. The most common fault? “Bubbles,” says Sjogren, with a shudder. Sjogren hates bubbles. “If there’s one bubble, we’ll reject it.” Since I clearly have no future making glass, perhaps I can help with quality control. Except, rummaging through the rejection bin, I find units with bubbles so small that I can only see them when Sjögren points them out.

Fortunately, the high rejection levels don’t create waste: rejected units are simply melted down and used again. “Sustainability is really important to us,” says Sjogren.

By Sjogren’s count, each gear selector is checked at least six times before being shipped to Volvo, ready for installation into a car. The multitude of checks is partly for standards, and partly due to the challenge of meeting the exacting regulations required for car parts.

“It’s not easy being a supplier to a car firm,” says Sjogren. “We have to be able to guarantee the production of every gear selector is the same. We’re not an automobile manufacturer: we make glass tableware. It took a lot of help from Volvo to sort.”

The gear selectors also had to undergo extreme temperature tests and prove they could survive when a Volvo was driven on extremely bumpy roads – not tasks usually required from, say, a champagne glass. So far, not a single selector has broken. “It will never happen,” says Sjogren. “Never, never, never.”

Both companies think the effort is worth it. “It’s helping us to become more innovative and raise awareness of our firm,” says Orrefors boss Ulf Kinneson. “It shows what else we can do.”

The pride shines through, as does the amount of effort that goes into production – for something that is, essentially, entirely unnecessary. Except that in a world ever more focused on technology, the glass gear selectors are a tangible link to something more solid. “It’s something real customers can hold onto,” says Bergstrom. “Crystal glass is a cutting-edge, timeless material – but we’re using it in a new way.”

It’s a material world: unusual materials in car production

Going for gold: If crystal glass isn’t exclusive enough, how about making car parts from gold? That’s what McLaren did when it created the F1 back in 1992. Borrowing concepts from its grand prix cars, it finished the heat shield for the F1’s V12 engine with gold foil. That wasn’t just to show off: gold is excellent at absorbing heat.

Going beyond gold: But if gold still isn’t exclusive enough, how about ruthenium? It’s an ultra-rare precious metal from the platinum group, with only a limited amount produced. It’s used to craft the ‘gallery’ of the ultra-luxurious Rolls-Royce Phantom Gentleman’s Edition, created by the British firm’s Bespoke arm.

Bentley’s 4800-year-old interior: Bentley teamed up with the Fenland Black Oak Project charity, which is creating a 13-metre table out of a 4800-year-old Fenland Black Oak reclaimed from former swampland in East Anglia. Strips of the material featured inside the Bentley EXP 100 GT concept car – although, given the scarcity of the wood, wider usage is unlikely. Still, wood is an integral part of many cars: Morgan machines still feature frames crafted from ash.

Seatbelts made from seatbelts: As sustainability becomes more important, car firms are increasingly using recycled materials in their cars. The new Renault Zoe features seatbelts and other interior trim produced using a recycled fabric made from plastic bottles, textile strips – and old Renault seatbelts.

RELATED ARTICLES

RSB Group Prepares for Hyper-Growth: New Markets, Tech and Mission ₹10,000 Cr

From a small workshop in Jamshedpur to an engineering group with global reach, RSB Transmissions is preparing for its mo...

Beyond Helmets: NeoKavach Wants to Make Rider Airbags India’s Next Safety Habit

As premium motorcycles proliferate and riding culture evolves, an Indo-French venture is betting that wearable airbags, ...

Inside Mahindra Last Mile Mobility’s Rs 500 Crore Modular Platform Strategy

Mahindra Last Mile Mobility has launched the UDO, an electric three-wheeler built on a new Rs 500-crore modular platform...

30 Dec 2019

30 Dec 2019

20569 Views

20569 Views

Darshan Nakhwa

Darshan Nakhwa

Shahkar Abidi

Shahkar Abidi