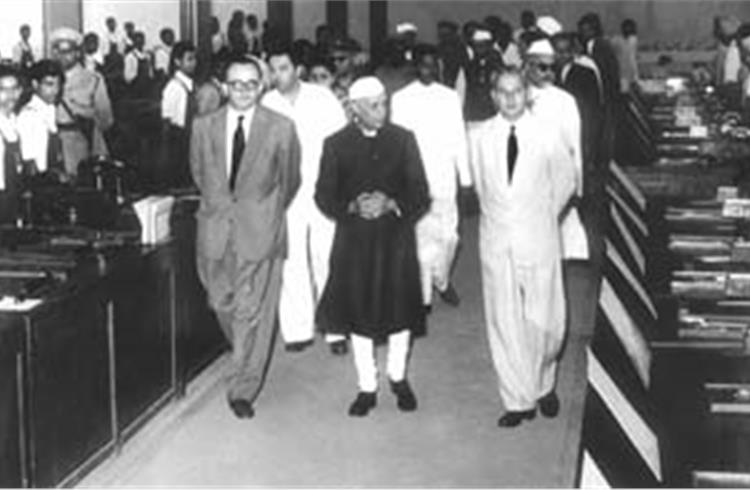

How the wheels were set in motion

While the auto landscape today is different from what it was in the 1940s, one must not forget the efforts of those visionaries who kicked off the revolution in India.

When Jawaharlal Nehru gave his stirring Independence Day speech on August 14, 1947, visionaries like BM Birla and Walchand Hirachand had already set up shop to start complete manufacture, rather than just assembly operations, of automobiles in India. Having been under English rule for centuries, it was only inevitable that India’s entrepreneurs looked at British cars for reference points.

WHEN IT ALL BEGAN

Birla established Hindustan Motors (HM) in 1942 to manufacture certain components, but started making cars only in 1949. HM later tied up with UK’s Nuffield to make the Morris, which was christened Hindustan here in India. Then came the Hindustan 14 (Morris 14) and Baby Hindustan (Morris Minor). HM brought out the Landmaster in 1954.

However, the real success for HM came in 1957 when it moved entire toolings of the next generation Morris Oxford (Series III) to India, after the car was withdrawn from the UK market. This was the birth of the Ambassador, a car which became the official vehicle of the entire government and its many departments, ensuring it a smooth ride over the years with very little changes made to the original Amby. HM entered truck-making in 1959 when it signed a deal with Vauxhall to make Bedford trucks.

The journey for Hirachand though was not all that easy. He had started discussions with Chrysler back in 1937 to set up an automobile assembly plant. Since carmaking was not part of the war effort, it took him seven long years to convince Mumbai’s bureaucratic circles and at last set up Premier Automobiles (PAL) in 1944. Hirachand made up for lost time quickly, and in only two years, rolled out the Dodge DeSoto and Plymouth cars from PAL’s Kurla plant in Mumbai. This gave PAL the distinction of being the first Indian automobile manufacturer.

In the initial days, the company started making Dodge trucks which ensured a steady flow of army orders. PAL started making cars in 1951 when it signed an agreement with Fiat to make the Fiat 500 and later Millecento and Fiat 1100, the age old Padmini of today, in 1954. However, PAL faced stiff competition in the small car sector from Standard Motor Products of India (SMPIL) at the time. SMPIL of course went out of business eventually. In the mid-1960s, after the wars with China and Pakistan, the government decided to make its own trucks and forced PAL out of the truck business.

While both HM and PAL concentrated on making passenger cars, the Mahindra brothers – Kailash and Jagdish Chandra – along with Ghulam Mohammad (who later became the first Finance Minister of Pakistan) set up Mahindra & Mohammad in 1945 to make utility vehicles. On his trip to the United States as chairman of the India Supply Mission, KC Mahindra met with Jeep’s inventor Barney Roos, and decided to make the vehicle in India.

M&M's EARLY DAYS

Post-independence in 1947, the company changed its name to Mahindra & Mahindra. M&M imported the first batch of 75 CJ2A and CJ3A Jeeps during the country’s first year of independence. It rolled out the first Indian-built Jeep from its plant in Mazgaon in 1949. When the time the government rationalised the industry in 1954, M&M was the only company making Jeeps and utility vehicles. Hence, it easily received approval to make 3,000 Jeeps. It remained the only player in this segment for the next forty years.

M&M entered the commercial vehicles segment in 1968. The 1973 oil crisis forced the company to look at a diesel engine option, which first came in the form of the MD-2350 International Harvester (from its tractor division) fitted onto the CJ500D and later through Peugeot’s XDP 4.90 engine on vehicles in the mid-1980s. One must also not forget Tata Engineering & Locomotive Company (Telco) in this scheme of things. Sumant Mulgaonkar, the man at Telco’s helm from 1949-89, was key to the company’s vision and success. Set up at Jamshedpur in 1945, Telco first ventured into making steam locomotives for the Indian Railways.

The company received government sanction in 1954 to make commercial vehicles, and so entered into a 15-year technical and financial collaboration with Daimler-Benz. The first truck out was the 312 Series, a current model in Europe. The model was named TMB (Tata Mercedes Benz) 312 and equipped with Daimler-Benz’s OM312 engine. An instant success because of its five tonne payload and diesel advantage, it was a far cry from the 3.5 tonne petrol Bedford, Ford and Cheverolet trucks of the time. Daimler-Benz constantly transferred technology to Telco, eventually leading to localising the TMB 312 in eight years’ time.

##### TELCO'S ENGINE FORAY

Telco’s first engine was the 692-DI, India’s first direct injection engine. Although it was an instant success, the engine was a copy of the OM312 and thereby a cause of some frustration for Daimler-Benz. The real parting came when Telco wanted to export this vehicle to the same markets as Daimler-Benz.

The collaboration ended in 1969 and the company was on its own selling trucks with the Tata brand name. Not holding back, it entered the light commercial vehicles segment in 1985 with the launch of Tata 407. The LCV took on superior technically advanced Japanese vehicles and gaining 70 percent market share in the process.

The contribution of India’s young automobile manufacturers and their innovative entrepreneurs is all the more glaring, especially taking into account the unfriendly policies of the time. From the outset, it was clear that private vehicle ownership was did not rank high on the minds of Independent India’s leadership. The nation had just woken up to the sweet dawn of freedom. The need of the hour was to “take the pledge of dedication to India and her people and to the still larger cause of humanity” in the words of Nehru.

In an effort to be self-sufficient, policymakers chose the Soviet Union’s socialist ideals and central planning methods. This led to an isolation from the outside world, a result of policies which substituted imports through domestic products and even discouraged (if not banned) foreign investment. The powers that be also imposed a strict regime of licensing and discriminatory controls that later became known as the License Raj. Constraints on capacity, foreign collaborations, foreign exchange allocations, price controls and punitive taxes and tariffs were the order of the day.

The government appointed the first Tariff Commission in 1952 to look at an indigenous automobile industry. The result was the government ending activities of assemblers without any serious manufacturing operation in the country in the following year. By 1954, assemblers like General Motors and Ford decided to leave India.

MORE CONTROLS

Further setbacks came in 1956 when the government decided to restrict the type and make of vehicles to be produced in the country. This meant only three passenger cars, three medium trucks, one heavy truck, one Jeep and one light truck were allowed to be made. Even new entrants with a full-fledged manufacturing programme were denied entry. The industry’s excessive reliance on foreign technology prompted the government to appoint the Mudaliar Commission to look into the matter, which ended foreign equity participation in 1968.

The government's fixing of selling prices and dealer margins prompted the industry to take the case to the Supreme Court in 1969. The landmark case resulted in the government setting up the Car Price Commission to define a formula to allow for incremental price increases. This brought some relief to carmakers but price controls were completely abolished only in the 1980s. The broad banding scheme, which permitted the diversification into related products without obtaining new licenses, was introduced in 1985. The simultaneous arrival of Maruti Udyog brought about the winds of change in the Indian automobile industry.

With inputs from Hormazd Sorabjee

RELATED ARTICLES

BRANDED CONTENT: Eliminating the worries of battery charging with smart solutions

The charging infrastructure is the backbone of electric mobility but is also one of the key perceived barriers to EV ado...

The battery-powered disruptor

Greenfuel Energy Solutions is planning to shake up the EV battery market with the launch of a portfolio of specially eng...

SPR Engenious drives diversification at Shriram Pistons & Rings

The engine component maker is now expanding its business with the manufacturing of motors and controllers through its wh...

By Autocar Pro News Desk

By Autocar Pro News Desk

04 Sep 2007

04 Sep 2007

8417 Views

8417 Views