Bettered by design: behind the scenes at Land Rover's design studio

Engineering used to dictate form, but times have changed. We meet Land Rover’s design boss to discover why style is now equal to substance

Whatever your opinion of Land Rover design – and for most critics it’s distinctly warm – you can’t fault design director Gerry McGovern on the consistency of his philosophy.

When he took the director’s job back in 2004 after a few years of designing American luxury cars (and the first Freelander before that), he explained his design motivation to Autocar with crystal clarity. “Land Rover’s roots are in pure design,” he declared. “It’s not just about styling.”

On that score, nothing has changed. As we discovered during a conversation in the marque’s Gaydon ‘design garden’, McGovern is happy to re-state his philosophy as stridently as ever, despite all the water that has flowed under the bridge. Land Rovers are selling four times as well as they did when he first took the big job and today’s showrooms contain three or four more models than they did. Nevertheless, “visual durability” remains a core component of Land Rover appeal, even if you no longer need to stress it as you once did.

“After I came back to Land Rover, I worked in advanced design,” says McGovern, “and it gave me a chance to get my thinking straight. I’d always liked the marque, going right back to that famous photograph of Winston Churchill with the Series One and the cigar. These were not machines for car enthusiasts, but everyone knew about their integrity. I liked their sheer depth of character. Land Rovers started off looking as they did because of what they could do – which was fine for the time but it meant design played second fiddle to engineering.

“My view was that if you wanted compelling, emotional, modern designs to last in production, design had to be an equal partner with engineering. So we changed it. Now we’re equal partners.”

McGovern says he’s nowadays “joined at the hip” with Nick Rogers, Jaguar Land Rover (JLR) chief engineer, “even though we sometimes make life hard for him.” Modern engineers, he says with conviction, understand as well as anyone in the company the beneficial effect that appealing design has on sales.

We’re at Gaydon, overlooked by a gigantic jumble of cranes and scaffolding as the adjacent engineering centre is rapidly reconfigured as a happy home for 12,000 inmates. As well as spending time with McGovern, my mission is to meet Land Rover’s chief designer, colour and materials, Amy Frascella, because Land Rover has rapidly become an influential leader in this vital area and American-born Fraschella is recognised as one of its foremost experts.

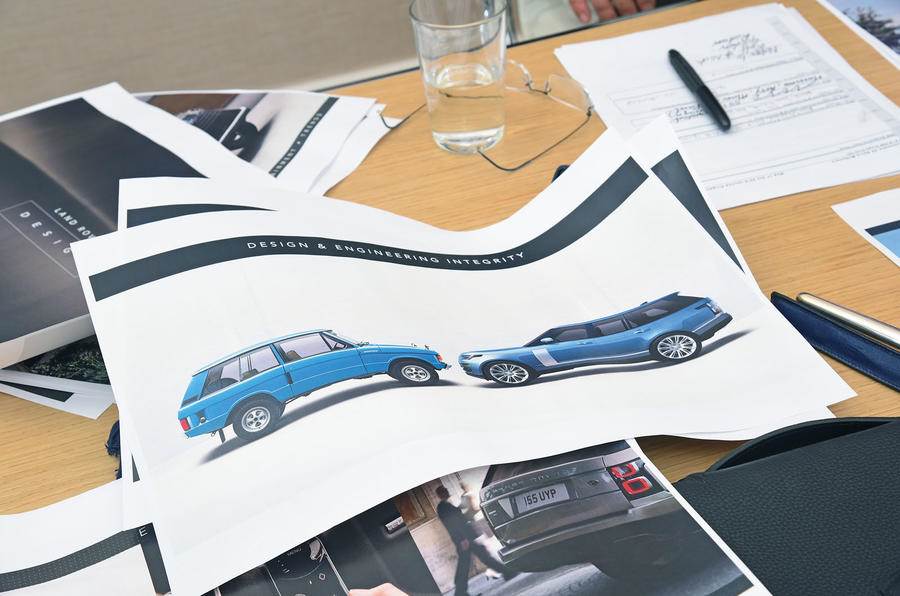

Parked around us are four Land Rovers: a superb Series One from JLR’s Reborn operation; the actual LRX concept that wowed the world at Detroit in 2008 and rapidly turned into the rule-changing Evoque three years later; a mid-1970s two-door Range Rover (in the mustard colour that only ever looked good in this solitary application); and McGovern’s own motor of the moment, a matt-finish Range Rover in Byron Blue. A more disparate quartet would be hard to find.

The two design chiefs are thus looking wary because they know our story’s remit is to gather their thoughts on why Land Rovers look the way they do, a gigantic question. It’s clear they’re not keen to grope for links between the machines they create today and cars from 1948, or even 1970.

Yet it has to be asked: what do these Land Rover and Range Rover originals mean to my companions? McGovern, famous for having his head in the future, smiles a little wearily as he acknowledges a fondness for the classics and their contribution to Landie DNA, “though the world’s changed massively since then”. Frascella acknowledges the honesty and durability of materials in early cars and reckons their intended longevity still influences today’s materials choices. Neither designer puts it this way, but it’s pretty clear that as long as new Land Rover models acknowledge original marque values, and do them no actual harm, the job’s done.

For both, the LRX is where true relevance to today begins. “This concept brought me into the brand,” says Frascella, who was working for a Korean brand at the time. “It was such a disrupter. I saw it in Geneva, and then as a production model in LA. It made me curious about what they’d be doing next.”

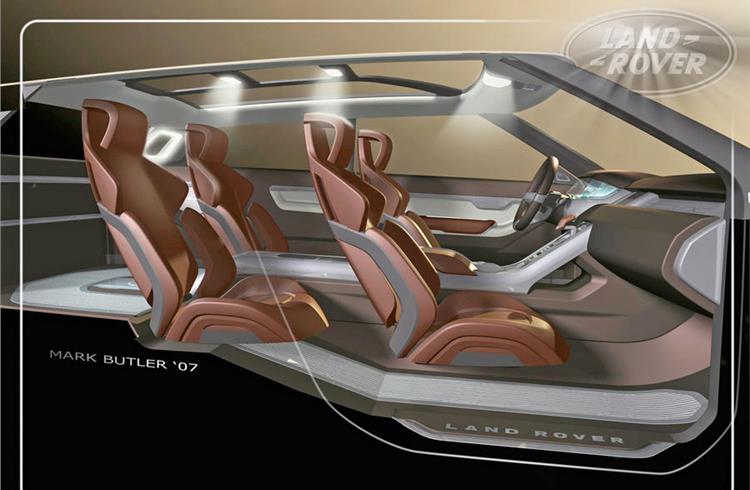

Frascella’s major task today is recognising, and preferably setting, the colour and material trends of the future. She’s already well known for creating luxury interiors for a post-wood-and-leather audience and recently introduced a ‘premium textile’ called Kvadrat into the Velar as an alternative to leather. Buyers are nowadays very knowledgeable about the sources of their cars’ materials, she says, and there’s a shift in favour of reclaimed and non-leather materials in what she calls “post-industrial” colours. “Premium car customers still love luxury,” says Frascella, “but they’re also dialling back the consumerism and doing some good if they can.”

McGovern makes the principles of good design sound deceptively simple. “It’s all about ideal volumes and proportions,” he says, brandishing two fascinatingly different profile illustrations of a current Range Rover, one as it should be, the other with incorrect details and proportions. They’re from a presentation McGovern often makes to Land Rover insiders selling the best design principles.

The standard picture shows correct body overhangs (short front, longer rear), an ideal ship-in-full-sail stance, desirable (big) wheels and neat bodyside details that add class. The second is the same car on small wheels with its proportions all over the place. It so obviously lacks the balance and elegance of a Range Rover that, for McGovern, “it almost attacks the senses”.

He says: “You still see plenty of cars that were engineered before they were designed and the risk is they come out like this. Design is about discipline. You have to do things the right way: first get the volumes and proportions right, then work on the stance, then make sure the surface development delivers the elegance you want, and then add details. Then it’s a matter of honing a new vehicle for production, a painstaking job. That’s very much a team effort, and it always has been.”

He says: “You still see plenty of cars that were engineered before they were designed and the risk is they come out like this. Design is about discipline. You have to do things the right way: first get the volumes and proportions right, then work on the stance, then make sure the surface development delivers the elegance you want, and then add details. Then it’s a matter of honing a new vehicle for production, a painstaking job. That’s very much a team effort, and it always has been.”

RELATED ARTICLES

Driving EV business with agility and flexibility

CEOs from the EV startup ecosystem met in Bengaluru and Pune to discuss the challenges and business opportunities.

BRANDED CONTENT: SM Auto and Gotech energy inaugurate their first battery pack assembly plant in Pune

Pune-based SM Auto Engineering (SMA), a leading automotive component system manufacturer and its partner Gotech Energy (...

Safer toys for India: Behind the scenes at Centy Toys’ factory

Autocar India explores the safety norms that govern the making of scale model cars at Centy Toys.

09 Dec 2018

09 Dec 2018

6657 Views

6657 Views

Autocar Pro News Desk

Autocar Pro News Desk